The early history and appearance of The Church of The Holy Sepulchre remain uncertain, owing to the many changes that have taken place on the site and the impossibility of thorough excavation.

All architectural development was conditioned by the Crucifixion (Calvary) sites and the Tomb of Christ in a former stone quarry.

Fixed points of lesser significance were the grotto now known as the Prison of Christ and St Helena’s crypt, the underground cave where St Helena discovered the Cross.

After the rediscovery of the Holy Places by Constantine in 326, they immediately became the focus of Christian veneration.

Both the Calvary and the Tomb of Christ were isolated by cutting away the surrounding rock and earth, making them free-standing blocks.

Between 326 and 337, the Tomb of Christ was surrounded by the so-called Anastasis Rotunda. East of this was a roughly rectangular courtyard, surrounded by a peristyle, with Calvary forming the southeast corner and the Prison the northeast corner. To the east of the courtyard was a sizeable five-aisled basilica, its apse facing west and enclosing the crypt of St Helena.

The details of the 4th-century layout are still disputed, but the outlines of the scheme are generally agreed upon. The main elements were all reasonably traditional, notably the rotunda enclosing the Tomb, which derived directly from royal and imperial mausolea. Still, the combination of rotunda, courtyard, and basilica was most unusual.

Although the three elements can be described separately, the site was always conceived as a unified whole. The rotunda consisted of a massive exterior wall containing three small apses at the cardinal points (except the east, which faced onto the courtyard).

Within was a two-story circular colonnade, forming an ambulatory around the Sepulchre. The structure may originally have been unroofed, but it was undoubtedly covered by the end of the 4th century.

Much of the Constantinian masonry of the outer wall survives, but the internal columns, although retaining their original disposition, have been replaced. In front of the rotunda was a stone-paved courtyard surrounded by a colonnaded walkway.

The rock of Calvary projected in the southeast corner and was surmounted by a great cross. A small chapel, the church of Golgotha itself, was situated south of the rock. The main church was Constantine’s great Basilica, also known as the Martyrium, east of the courtyard.

The apse, at the west end and adjoining the courtyard, has been excavated, while two of the doors of the atrium, which preceded the basilica to the east, survive as foundations within later buildings. This gives a total length for the basilica and atrium of 75 m. It had double aisles, surmounted by galleries, thus resembling the Constantinian Basilica of St Peter in Rome.

The roof was of wood, and the whole was, according to Eusebios of Caesarea, magnificently decorated, sheathed in marble, and with a coffered ceiling painted in gold.

The result was a splendid group of buildings; the early pilgrim would have approached a triple gateway and entered the basilica’s atrium, a large colonnaded courtyard. Beyond this was the basilica itself, splendidly adorned and sheltering St Helena’s crypt.

A door at the end of the basilica led into a second colonnaded court containing the rock and cross of Calvary, the shrine known as the Prison of Christ, with the rotunda rising on its far side.

Since Constantine’s time, the site has undergone many changes. In 614, Jerusalem fell to the Persians, and the Holy Sepulchre and associated buildings were sacked. The Patriarch Modestus carried out restorations, and the Christian shrines survived the Arab conquest of 638.

In 1009, however, the fanatical caliph al-Hakim ordered the systematic destruction of the Holy Sepulchre. The basilica was entirely demolished, and Calvary and the Sepulchre mutilated, but somewhat surprisingly, the external wall of the Anastasis Rotunda seems to have been left largely intact.

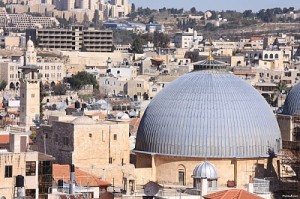

After several years of desolation, the Byzantine rulers of Constantinople obtained permission to restore the site, and the work was completed in 1048, during the reign of Constantine IX Monomachos. The rotunda was rebuilt, using the surviving Constantinian walls, but with the addition of a gallery at the first-floor level and the insertion of a tall apse on the eastern side.

A conical timber roof covered the whole structure, thus becoming a centrally planned Byzantine church rather than a Roman mausoleum. The courtyard to the east, containing the sites of Calvary and the Prison, was also restored, remaining an open space and closed on its eastern side (where the basilica had stood) by a wall containing three small apses.

The complete disappearance of the basilica meant that the whole site was now oriented. The courtyard must have somewhat resembled a cloister, with a colonnaded walkway on three sides, surmounted by a gallery linked to the new rotunda gallery. The main entrance to the site was on the south side of the courtyard.

After 1099

When the Crusaders conquered Jerusalem in 1099, their immediate concern was to restore and beautify the Holy Sepulchre further, and work began shortly after the conquest. It was completed by the 50th anniversary of the fall of Jerusalem, for it was consecrated on that day, 15 July 1149.

The crusader plan was, in essence, simple. It was to enclose the open courtyard in a new, roofed structure, which would form the transepts and chancel of the church, with the rotunda remaining and taking the place of a nave.

The ground plan of the new part of the church was a familiar Romanesque one, the east end consisting of an apse and ambulatory, with three radiating chapels.

Calvary was enclosed by the south transept, the Prison by the north, and a passage from the ambulatory led down to the crypt of St Helena. The Byzantine apse was demolished to join the rotunda with the rest of the church.

Architecturally, the crusader church was an amalgam of various Western design features. Built chiefly of limestone, it had two stories of equal height, consisting of a main arcade and gallery.

The arches were lightly pointed throughout, and quadripartite ribbed vaults with a dome over the crossing covered the transept arms and choir.

The elevation and vaulting suggest Burgundian and northern French origins. The main entrance to the church, the south transept façade, has been compared with the south transept doorways of Santiago de Compostela and St Sernin, Toulouse.

The Crusaders made a considerable effort to preserve what they believed to be the original fabric of the church, notably in the rotunda and the north transept, where a section of the 11th-century courtyard arcade remains.

The whole interior of the building was most lavishly decorated in mosaic and paint, while the south transept façade was elaborately decorated with sculpture.

The Sepulchre itself was enclosed in a sumptuous aedicula, constructed of marble and intricately carved.

There is some reason to believe that the north transept was completed after the consecration. In the second half of the 12th century, a cloister was added east of the central apse and over the roof of St Helena’s Chapel.

The conventual buildings for the Augustinian canons of the Sepulchre surrounded the cloister itself. The bell tower, adjacent to the south transept façade, was added simultaneously.

After the fall of Jerusalem in 1187, the church was spared, but it suffered some wilful damage and considerable neglect.

The claims of the competing Christian denominations caused the building to be partitioned into separate areas. This contributed to a disastrous fire in 1808, which destroyed much of the fabric.

Further severe damage was caused by the restorations that followed the fire when much of the east end was entirely rebuilt. The present structure replaced the crusader aedicula over the Sepulchre.

The building was threatened further by a severe earthquake in 1927 when the rotunda had to be shored up with scaffolding.

The complete restoration did not begin until 1962, but now the visitor can get some impression of the historic nature of the building and of its component parts.

The Romanesque transepts and ambulatory survive, with the 19th-century choir. The rotunda retains something of its Byzantine appearance, and the Constantinian masonry is visible in its outer walls.

The mass of surrounding buildings swallows up the church, the only clear space from which it can be seen being the parvis in front of the south transept.